Greetings, beer-lovers!

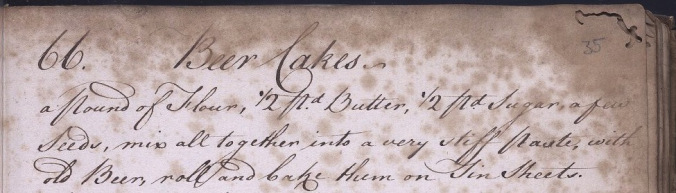

As we discussed not long ago, one of beer’s many wonderful qualities is its versatility! Here at the Black Creek Growler, we do enjoy cooking with our beer. Although this didn’t happen that frequently in the 1800s, beer adds some pep to modern-day recipes!

And so, I embarked on a quest for Boston Beer-Baked Beans. As usual for me, I combined several recipes based on availability of ingredients and my preferences. Now, without further ado:

Boston Beer-Baked Beans (Vegetarian)

- 1 can beans (they’re meant to be navy beans, but I only had mixed beans)

- ½ cup beer (not dark)

- 1 medium chopped onion (I had two teeny onions)

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1/3 cup ketchup

- 3 Tbsp molasses

- 2 tsp Worcestershire sauce

- Drizzle olive oil

- ½ tsp paprika

- ¼ tsp cayenne pepper (or to taste)

- ¼ tsp black pepper.

Let’s talk about the beer. According to most recipes I found, most light beers will work. Personally, I’d go for something a little hoppier and more bitter, to cut through the molasses’ thickness and sweetness. So probably a pale ale, as opposed to a light lager. Being lighter in flavour generally, pale ales also balance nicely with most recipes.

Ideally, of course, I’d be using Ed’s Pale Ale, brewed at the Black Creek Brewery. Alas, it is March, not July, and so I had none to hand. I compromised by using Molson’s 1908 Historic Pale Ale. It’s an unfiltered beer based on a recipe from 1908. I mean, it’s not an 1830s recipe, but it’s a perfectly serviceable pale ale. Which, in this context, I count as high praise.

Anyway, once the ingredients are assembled, the recipe is simple:

- Drain and rinse beans

- Combine other ingredients in a large bowl

- Mix beans in

- Bake uncovered at 350°F until most liquid is absorbed: about 40 minutes.

It smelled really, really good while baking. Like, the molasses aroma definitely filled my apartment, but I could get hints of beer underneath. It reminded me of being in the brewery while Ed’s boiling the wort.

I wasn’t sure if I’d overdone the baking, but the result tasted good! Sweet and savoury, with the beer’s sharpness cutting through and adding a lovely counterweight. Paired with some corn bread, it’s definitely something I’d make again…ideally, with Ed’s Pale Ale (or maybe his IPA—I bet the citrus flavours would give it a nice zing!).

Until next time, beer-lovers!

Katie