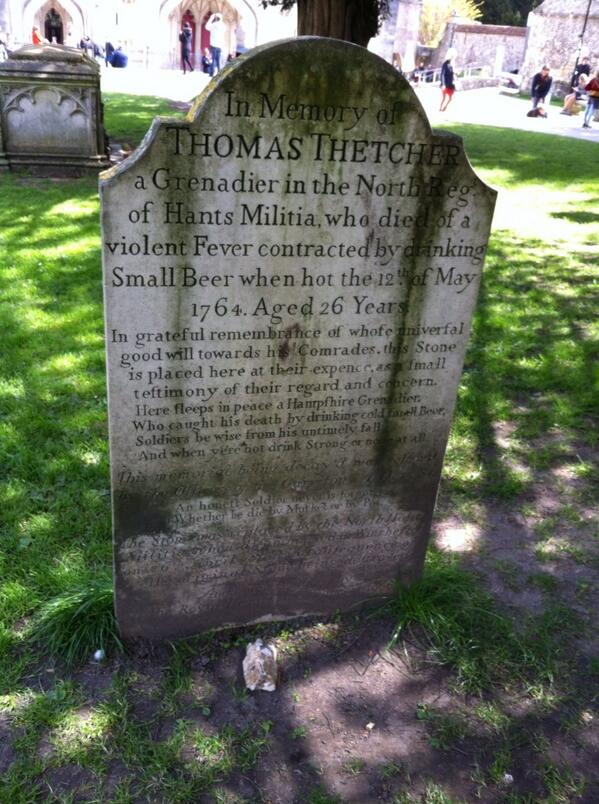

It all started with this photo:

My boss sent it to me, adding, “…read as much of the small print as possible.”

Luckily for my eyes, the full text is available elsewhere:

In Memory of Thomas Thetcher a Grenadier in the North Reg. of Hants Militia, who died of

a violent Fever contracted by drinking Small Beer when hot the 12 May 1764. Aged 26 Years.

In grateful remembrance of whose universal good will towards his Comrades, this Stone is placed here at their expence, as a small testimony of their regard and concern.

Here sleeps in peace a Hampshire Grenadier,

Who caught his death by drinking cold small Beer, Soldiers be wise from his untimely fall

And when ye’re hot drink Strong or none at all.

What? How did the beer kill him? Did it have something to do with the temperature, or was it the “small” (low-alcohol) nature of the beer? Your trusty beer journalist cannot resist a history mystery like this, so of course I’ve spent the last three days digging. What killed Thomas Thetcher?

Let’s look at three possibilities: food/beer poisoning, mould, and contaminated serving vessels.

Food/Beer Poisoning

Is it possible that Thetcher’s beer was contaminated? My first instinct was to say, “No, in the 1700s, beer was likely safer than water.” After all, boiling the wort kills most bacteria, hops have some antibacterial properties, and fermentation drops the pH to a level where most bacteria can’t survive. One exception is the bacterium Acetobacter, which can survive well under 5.0 pH—beer tends to be around 4 pH, unfermented beer around 5.1-5.4.

But all Acetobacter does is convert the alcohol in beer into vinegar. Drinking vinegar wouldn’t have killed Thetcher, and anyway, he would’ve noticed the taste at the first sip.

A few other strains of lactic acid bacteria can survive in beer, but again, they just produce off-tastes and odours.

I did wonder if the “small” nature of the beer might have allowed for something else to take hold. What if this beer was low enough in alcohol that other bacteria could survive? Maybe this is what the militia meant when they declared drink Strong or none at all?

However, the boiling process still poses serious problems for bacteria. Let’s look at the most commonly troublesome ones:

Salmonella generally grows from 7-48 degrees Celsius, with optimum pH around 6.5-7.5. Between the rolling boil and acidic nature of even unfermented beer, it would die.

E. coli? More acid resistant, but can grow to 49 degrees Celsius. It would die.

Listeria? Optimum growth temperatures range from 4-37 degrees Celsius. It would also die (surprise!).

So…it seems that the small beer would leave the brew-kettle free of bacteria, which means Thetcher didn’t die from a bacterial infection.

But what happens after the beer leaves the brew-kettle?

Mould

I got really excited when I discovered that Britain experienced very wet summers from 1763-1772. Probably too excited, but that’s all right.

You see, mould likes damp conditions. Mould also likes wood. Guess what’s made of wood?

These:

So, imagine our small beer arrives from the brew-kettle nice and sterile, and goes into the casks. The mould-contaminated casks. Not being a microbiologist, I wonder if the relatively low-alcohol environment of a small beer might have allowed for some mould growth.

Penicillium mould can grow in and through the joints and bung holes of wooden barrels, infecting the beer inside. It’s usually not dangerous if you’re healthy—unless Thetcher had a penicillin allergy? (I assume he would immediately taste it, but maybe it was really hot and he was really thirsty.)

Looking earlier in the brewing process, Fusarium is another fungus that infects cereal crops, including barley. Moreover, Fusarium makes a fun little mycotoxin called Deoxynivalenol (DON). The fungus itself is killed when the malt is kilned, but the toxin it produces can survive malting, kilning, boiling, and fermentation.

I got really excited again…but it turns out that DON is more dangerous for livestock eating contaminated feed than it is for humans drinking contaminated beer. Short-term, humans may experience some nausea, headache, and fever after eating infected grains, but the long-term health effects of drinking beer made from Fusarium-infected barley have yet to be determined.

So, Thetcher likely didn’t die from Fusarium either.

Contaminated Serving Vessels

One more theory.

In pubs today, it is actually really important that draught beer lines are kept clean. Yes, you can get foodborne illness from beer. Dirty pipes accumulate yeasts, bacteria, and moulds that may well survive the trip from your beer glass to your digestive tract.

I suspect that early beer engines (invented in the late 1600s) were difficult to clean.

Likewise, we have a sanitizing dishwasher. Thetcher’s local watering hole didn’t. Perhaps the issue was not the beer, but rather the manner in which it was served—perhaps a mug wasn’t washed, or a mug held E.coli-infected water and then Thetcher’s small beer.

Cross-contamination and subsequent foodborne illness seems plausible to me.

So what killed Thomas Thetcher?

Ultimately, we’ll never know. It’s just as likely that he caught a completely unrelated fever and died, leaving his compatriots to unjustly malign small beer.

But if we’re speculating…

I would speculate cross-contamination of serving vessels. Think of it this way: alcohol “kills bacteria,” but would you keep drinking your sample if I tossed a piece of raw chicken in there?

I thought not. Now imagine that instead of drinking a 5% beer, you have a 1-2% small beer.

It’d still require a huge amount of bad luck, but not an impossible amount.

Otherwise…this is even less likely, but the damp conditions that characterized the 1760s may have led to increased mould growth on the beer casks. If that mould included Penicillium, if it got into the beer, and if Thetcher was unlucky enough to have a severe penicillin allergy…well, it’d be hugely unfortunate, but not totally impossible.

And with that ringing endorsement, we have not solved this history mystery to my satisfaction…but we’ve learned that beer is remarkably resistant to pathogens!

-Katie

Further Reading/Sources

deLange, A.J. “Understanding pH and its Application in Small-Scale Brewing,” More Beer, July 18, 2013, accessed April 22, 2014.

Donaldson, Michael. “A kick in the guts,” Stuff.co.nz, September 15, 2013, accessed April 23, 2014.

Doyle, M. Ellin. “Fusarium Mycotoxins,” Food Research Institute of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, December 1997, accessed April 22, 2014.

Jones, Kendall. “The Elephant in the Room: Dirty Draft Beer Lines,” Washington Beer Blog, August 22, 2012, accessed April 23, 2014.

Pambianchi, Daniel. “Keeping it Clean,” Brew Your Own: The How-To Homebrew Beer Magazine, Jan/Feb 2008, accessed April 22, 2014.

Sobrova, Pavlina, et. al. “Deoxynivalenol and its toxicity,” Interdisciplinary Toxicology 3:3 (Sept 2010): 94-99, accessed April 22, 2014, doi: 10.2478/v10102-010-0019-x

n.d. “1750-1799,” Meteorology at West Moors. accessed April 22, 2014.